Background

The security committee of The Apache Software Foundation (ASF) oversees and coordinates the initial triage, handling, and process around vulnerabilities across all of the 320+ Apache projects handling over 65 incoming emails a day. Established in 2002, we have a consistent process for how issues are handled, and this process includes how our projects must disclose security issues. We have a single paid person to help deal with incoming vulnerability handling work, with the rest of the team, including the VP, being volunteers.

Anyone finding security issues in any ASF project can report them to security@apache.org, where they are recorded and passed on to the relevant dedicated security teams or private project management committees (PMCs) to handle. These groups are composed wholly of volunteers. In general; each community, or PMC, is responsible for handling their own vulnerabilities. The security committee monitors all the issues reported across all the projects and keeps track of the issues throughout the vulnerability lifecycle. It also helps the various communities with their security response and process. And finally, the security committee reports on this to the ASF Board as part of the ASF oversight and governance function.

The security committee is responsible for ensuring that issues are dealt with properly and actively reminds projects of their outstanding issues and responsibilities. Our paid person plays a pivotal role here. As a Board committee, we have the ability to take action including blocking a project’s future releases or, worst case, archiving a project if such projects are unresponsive to handling their security issues. This, along with the Apache License v2.0, are key parts of the ASF’s general oversight function around official releases, allowing the ASF to protect individual developers and giving users confidence to deploy and rely on ASF software.

The oversight we have into all security reports, along with tools we have developed, gives us the ability to easily create metrics on the issues. Our last report covered the metrics for 2022. As well as vulnerability handling, this report also summarises the security initiatives we’ve worked on in the year.

Reporting Statistics for 2023

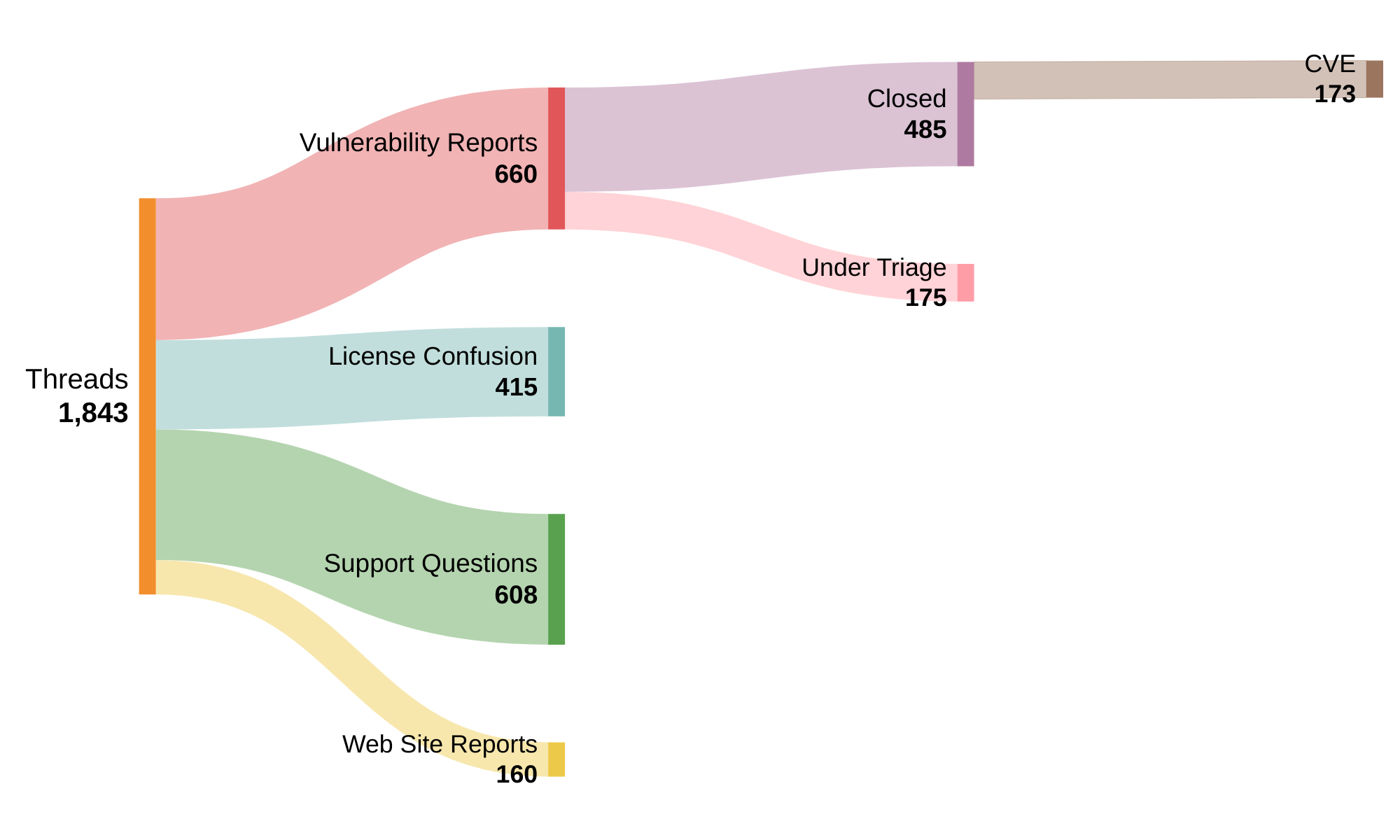

In 2023 our security email addresses received in total just over 24,000 emails (2022: 22,600). After spam filtering and thread grouping there were 1843 non-spam threads (2022: 1402, 2021: 1272, 2020: 946). Unfortunately security reports do sometimes look like spam, especially if they include lots of attachments or large videos, and so we are careful to review all messages to ensure real reports are not missed.

Diagram 1 gives the breakdown of those 1843 threads. 415 threads (23%) were people confused by the Apache License. As many projects use the Apache License, not just ASF projects, people can get confused when they see the Apache License and they don’t understand what it is. This is most common, for example, on mobile phones where the licenses are displayed in the settings menu, usually due to the inclusion of software by Google released under the Apache License. We do not reply to these emails. This is up significantly from the 305 we received in 2022.

The next 608 of the 1843 (33%) were email threads with people asking non-security (usually support-type) questions, questions about dependencies, or general administrative threads.

The next 160 (8%) of those reports were researchers reporting infrastructure issues such as those affecting our web sites. These are almost always rejected; where a researcher reports us having directory listings enabled, source code visible, public “.git” directories, and so on. These reports are generally the unfiltered output of some publicly available scanning tool, and often come along with a request for some sort of monetary reward (bounty).

That left 660 (36%) reports of new vulnerabilities in 2023 (up from 2022: 599, 2021: 441, 2020: 376), which spanned 112 of the top-level projects. These 660 reports include both external reports, as well as issues found internally by projects and their communities. We don’t keep track of the breakdown between those categories. For example, where a project has found an issue themselves they will follow the same ASF process to assign it a CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) name and address it, and we still count it here.

The next step is having the project triage the report to see if it’s really an issue. Invalid reports and reports of things that are not actually vulnerabilities get rejected back to the reporter. Of the remaining issues that are accepted, they are assigned appropriate CVE names and eventually fixes are released.

As of January 1st 2024, 175 of those 660 reports were still under triage and investigation. This is where a project was working on an issue and had not yet rejected the issue or assigned it a CVE at that date. This number seems quite high but it does vary through the year and tends to be higher at the end of the calendar year, when many developers take holidays. It’s not uncommon for lower severity issues to take some time before they become part of a new release, so at any given time there will always be a number of issues open and currently being worked on. However, we’re watching this metric on a monthly basis as the number of issues still under triage and investigation rising faster each month is a sign that projects are falling behind in processing reports.

The remaining 485 reports (2022: 490, 2021: 391, 2020: 341) directly led to us assigning 173 CVE records (2022: 210, 2021: 183, 2020: 151, 2019: 122). Some vulnerability reports may include multiple issues, some reports are across multiple projects, and some reports are duplicates where the same issue is found by different reporters, so there isn’t an exact one-to-one mapping of accepted reports to CVE names.

The four projects with the most reports in 2023 were Airflow with 109 reports, Tomcat with 38 reports, Superset with 38 reports, and InLong with 27 reports. Airflow and Tomcat are part of the HackerOne Internet Bug Bounty program.

CVE Statistics for 2023

In 2023 we published 258 CVE records (2022: 245). These records consist of vulnerabilities found and triaged in 2023 (the 173 mentioned above), and vulnerabilities found in previous years (“under triage”) where the release that fixed them was made in 2023. The four projects with the most published CVE were Airflow with 47 CVE, Superset with 27, InLong with 23, and Tomcat with 10. Note, as always, that the number of released CVE has no correlation with a project being more or less secure, and we’ve not taken into account severity levels or timescales. Indeed, projects fixing their issues and releasing timely security updates is a sign of a healthy project.

The Apache Security committee handles CVE name allocation and is a CVE project Candidate Naming Authority (CNA), so all requests for CVE names in any ASF project are routed through us, even if the reporter is unaware and contacts the CVE project directly or goes public with an issue before contacting us. The Apache Security Team requires that all security issues in all our projects have published CVE records.

Noteworthy vulnerabilities and events

During 2023 there were a few vulnerabilities worth highlighting; either because they were severe and high risk, they had readily available exploits, or there was media attention. These included:

- Several vulnerabilities were added this year to the CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog. These mostly can lead to remote code execution:

- A fixed and published vulnerability in Apache ActiveMQ in October 2023, (CVE-2023-46604). This vulnerability also gained press attention due to it being widely exploited on installations that have not been upgraded, including by ransomware. The Metasploit framework had an exploit submitted for this issue.

- A flaw in Apache RocketMQ (CVE-2023-33246), fixed in May 2023. The Metasploit framework had an exploit submitted for this issue.

- A flaw in Apache Spark (CVE-2022-33891) fixed in a release in July 2022.

- A flaw in Tomcat if an attacker can reach JMX ports (CVE-2016-8735), fixed in a release in 2017.

- CISA also released their ‘2022 Top Routinely Exploited Vulnerabilities’ report in August 2023, mentioning malicious cyber actors continue to show high interest in Log4Shell, (CVE-2021-44228). Their ‘Additional Routinely Exploited Vulnerabilities’ table also lists some HTTP Server vulnerabilities and a follow-up on Log4Shell. Nucleus Security made a visual representation of vendors in CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities report. With 28 of the 989 vulnerabilities, Apache is visible on the chart.

- A number of vulnerabilities in Apache OpenMeetings gained attention, addressed in a release in May 2023.

- Some time ago Santuario worked with Zoho to diagnose an issue that turned out to be incorrect use of an outdated xmlsec (Apache Santuario). Zoho fixed their software and disclosed CVE-2022-47966 for it. Unfortunately one of their on-prem customers had not upgraded and was compromised. This was published as a CISA CSA in September 2023.

- A critical flaw in Apache Struts was disclosed and fixed in December 2023, (CVE-2023-50164).

- A critical flaw in Apache OFBiz was disclosed and fixed in December 2023, (CVE-2023-49070 and later update CVE-2023-51467). There are reports of this issue being exploited.

Security initiatives

As well as helping projects handle reports of vulnerabilities, we’ve worked on a number of security initiatives in 2023. These included:

- Working with projects to publish “security model” pages on their websites, which help users understand what to expect from the project security-wise, and help security researchers on where to best focus their efforts. Such pages were published for Apache Maven, Apache JMeter, Apache Commons, Apache PDFBox, and Apache Airflow.

- Reviewing the Common Platform Enumeration names (CPE’s) that were assigned to our CVE’s by the NIST’s NVD programme, and suggesting fixes to some inconsistencies/misclassifications we identified. We have stopped distinguishing between ‘incubating’ and ‘regular’ Apache projects in the CPE, to avoid missing associations.

- Working with NIST’s NVD programme to align their Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) classifications.

- A similar review of the GitHub Security Advisory (GHSA) database, reviewing artifact mappings and adding missing ones.

- Put into place an ASF-wide default vulnerability severity rating system.

- Engaging with the Trivy SBOM/security scanner project to discuss how we can help reduce noise and make security reports more accurate, possibly using VEX. This is challenging because it requires the scanner to have access to not just a list, but the graph of dependencies.

- Starting providing guidance for consistent software identification using schemes such as Purl and SWIG, so vulnerability information can more easily be shared by Apache itself as well as third parties. Such consistent naming is essential to improve the accuracy of SBOM and vulnerability scanning activities.

- Working with projects to start publishing SBOM/VEX/VDR information, including this year with the Apache Logging project and Apache Airflow project. We have set up an experimental platform to collect and aggregate SBOMs and information about advisories for 3rd-party dependencies. This is already populated with information from 257 artifacts across 13 Apache projects, which we plan to expand and use to get more actionable information.

- Participation in the Community over Code NA conference, among other conversations sharing the learnings from the formation of the Airflow security team.

- Working with OSTIF who are doing a security audit of Apache Commons, focusing on the Commons Codec, Commons IO, and Commons Lang components.

- Based on input from various parts of the ASF, we submitted a response in November 2023 to the White House Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD) Request for Information (RFI) on “Open-Source Software Security and Memory Safe Programming Languages”.

- Working with other parts of the ASF to offer considerable advice to policy makers of the EU working on acts and directives such as the Cyber Resiliance act.

Conclusion

The ASF projects are highly diverse and independent. They have different languages, communities, management, and security models. However one of the things every project has in common is a consistent process for how reported security issues are handled.

The ASF Security Committee works closely with the project teams, communities, and reporters to ensure that issues get handled quickly and correctly. This responsible oversight is a principle of The Apache Way and helps ensure Apache software is stable and can be trusted.

This report gave metrics for calendar year 2023 showing from the 24,000 emails received we triaged over 660 vulnerability reports relating to ASF projects. We published 258 CVE records. The number of non-spam threads dealt with was up 31% from 2022 with the number of actual vulnerability reports up 10%. We also highlighted a number of new security initiatives we’ve worked on including metadata consistency and SBOMs.

If you have vulnerability information you would like to share please contact us or for comments on this report use the public security-discuss mailing list.